No, Tetouan was not born from a military camp after the First African War

This week a book about the 160-year history of the district of Tetuán was presented in style, an interesting volume that brings together a good number of photographs about the district that has been prefaced and presented by the mayor himself. In Tetuán 160 years, as it is called, the widespread idea abounds that the origin of Tetuán must be found in the military camp that was established on land in the current district after one of the wars that Spain waged in Morocco, in 1860. During the presentation, a phrase came to light that is also found in a photographic exhibition that, simultaneously, has been launched at the Eduardo Úrculo Cultural Center: “The history of the Tetuán district is, perhaps, a one of the most beautiful of all the districts of Madrid since it has an epic and victorious origin”.

A few days ago, the twitter account of the Group for the protection of the historical heritage of Tetouan had devoted an entire thread to explaining what happened in May of that 1860 and to denying the biggest one: the event did not mean the birth of Tetouan .

The commonplace about the history of the district is based on a true historical fact (there was a brief camp on the land of what is now Tetuán although it did not imply any foundation) and has been reproduced in books and articles on the internet for a long time already.

The African War, or First Moroccan War (against the Sultanate of Morocco), took place between 1859 and 1860, during the governments of the Liberal Union in the reign of Elizabeth II. General Leopoldo O'Donnell, who was the President of the Council of Ministers and Minister of War, was the central character and would receive the most attention from the press at the time. After a series of military victories (the battles of Castillejos, Wad-Ras or Tetouan) an armistice was signed that soon became known to part of the Spanish population that, imbued with the patriotism carried by the press and the political class, they wanted the conquest of Morocco. . The territories of Ceuta and Melilla were expanded, Morocco recognized Spanish sovereignty over the Chafarinas Islands, the Sidi-Ifni fishery was obtained and the administration of Tetouan for a short period of time.

The military campaign was a boost to the government, and both it and the crown did not miss the opportunity to exploit it for propaganda. Leopoldo O'Donnell had the idea of replicating the camp that they had had for several months in Africa and then marching into Madrid. At first, it was thought that the camp would be installed in the Dehesa de los Carabancheles, but finally it was decided to do it in the Dehesa de Amaniel "between the Moncloa walls and the canal deposit, to the left of the Francia highway" . Although at that time it was more extensive, we can get an idea of the pasture by looking at what remains of it today: the Dehesa de la Villa. The camp broke up on May 10 and on the same day the soldiers who were not yet in the capital arrived by train.

The Duke of Tetuán himself (a title obtained by O'Donnell after the battle of the same name), generals, chiefs and officers, who were paid by the Crown for lunch and 50,000 cigarettes, went there. Queen Isabella II, who was in Aranjuez, went to Madrid and went to the camp on the 11th. Then he went to the palace to wait there for the troops. The press reported how the camp aroused the interest of many people from Madrid, who came by car or bus to see the soldiers and participate in the party.

The Madrid City Council, for its part, collaborated by dressing the city as a gala for the triumphant entry of the troops into it. Portraits, conveniently illuminated, of the participating generals, such as O'Donnell or Prim, as well as leading figures of the homeland (Felipe II, the Catholic Monarchs, Cardinal Cisneros, Columbus...) were arranged. The Congress of Deputies was illuminated, the Town Hall was decorated and the band from the Teatro Real played from the balconies of the Military Casino. The Consistory paid for a bullfight for the troops. “Bread and rice relief by means of vouchers to the needy classes” (La Discusión, 5-11-1860) were also provided and the students had vacations during these two days.

The troops entered Madrid according to military protocol, divided into their respective battalions and regiments. The tour followed the itinerary of the France highway, La Ronda, Puerta de Atocha, the Prado hall, Calle de Alcalá, Puerta del Sol, Calle del Arenal, Plaza de Palacio, de la Armería, Calle Mayor, Carrera de San Gerónimo and Royal Palace. Some notable men left their homes, like Prim, who did so from Calle de Alcalá, bathing in crowds. In Atocha, a triumphal arch was arranged for the passage of the heroes (an ephemeral architecture made by Valencians, skilled in these skills).

The place where they camped is described as follows in La corona de laurel, a collection of biographies of the protagonists of the war written by Manuel Ibo Alfaro in 1860 with a laudatory tone:

How to Use Leftover Pasta Water https://t.co/vCvls9q3vo

— wikiHow Recipes Thu Nov 03 17:59:21 +0000 2016

This Dehesa is an extensive plain, cut by some gentle hills that give it that picturesque and pleasant character typical of hollowed-out lands. The wheat green esplanades that cover some of its slopes gently swaying their emerald spikes at the impulse of the zephyr; the small buildings that can be seen scattered here and there in the distance, and some trees that draw their graceful foliage on the blue horizon, offer an extremely poetic aspect. La Dehesa de Amaniel is about a league away from Madrid, and the road that separates it from that town is also pleasant because of the continuous variety it presents.

The time that the soldiers were camped in the Dehesa de Amaniel was, therefore, less than two days (part of the 10th and the morning of the 11th, before starting the march to Madrid). The visit of the people of Madrid to the camp took place during this time, despite which there are publications that affirm that the vendors who came to supply the army formed a pioneer nucleus of inhabitants. Something, as you can see, impossible.

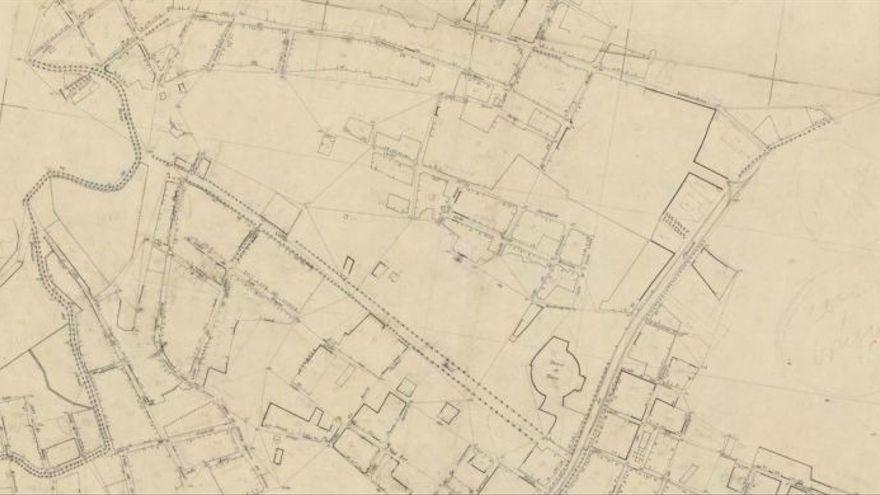

The map that I show here belongs to Tetouan in 1860 according to the date of the archive (Topographic Archive, General Directorate of the Geographic and Statistical Institute). It is possible that it is somewhat later, since the Plaza de Toros appears, which was built ten years later, but, as can be seen, at this point the urbanization was already very extensive and must have started much earlier. This can also be seen in other maps, such as the one contributed in the aforementioned thread by the Group for the Defense of the Historical Heritage of Tetouan. The primitive nucleus of what would be known as Tetuán had been born approximately between the current streets of Alonso Castrillo and Marqués de Viana, and at the height of 1865 it must have already been something more than seminal. On this date, Cayetano Rosell wrote in his Crónica de la provincia de Madrid regarding the area "that if it continues as it has started, it will shortly be a point of consideration, to which a multitude of buses attend daily, and especially on Sundays and holidays. that leave from the door of Bilbao leading people to the picnic areas that exist in that place”. In addition, to the west of the Francia highway you can also see a considerable extension of urbanization, towards what today would be Almenara and Berruguete.

Regarding the other large nucleus of what is now Tetuán, that of Cuatro Caminos, although it is true that the urbanization was still very small, we must take into account the buildings of houses and factories that had sprung up over the years 50 around the Francia highway (current Bravo Murillo street). The oldest construction licenses preserved in the Villa Archive (Martínez de Pisón, 1964) are from this period. In any case, the area where the soldiers camped, on the other side of the road, was quite far away.

In reality, the camp and the pilgrimage of Madrid residents who came to participate in the celebration in the Dehesa de Amaniel is a rather anecdotal fact and geographically separated from the incipient population centers north of Madrid, although it is true that it quickly spread constituted a nationalist story that permeated its growth, and that went through the name of the suburb of Chamartín de la Rosa as Tetuán de las Victorias, the change of name of the Carretera de Francia as O'Donell, the establishment of Nuestra Señora de las Victories as a religious matron a little later and the "conquest" of place names (from the Castillejos neighborhood itself to some streets, such as Topete or Wad-Ras). We are witnessing the ex novo creation of a tradition to probably symbolically endow a presence official to a peripheral territory under construction, de facto abandoned by the municipality. If we pay attention to the publications of the most progressive group of residents at the end of the century in the Tetuán neighborhood (a group of free thinkers, federal republicans and anarchists) we will find that they systematically flee from using the name Tetuán de las Victorias (which is beginning to be recorded written in the 1970s) and they always refer to Tetuán de Chamartín, something that tells us about their awareness of what the colonial narrative had as a cultural battle in the neighborhood.

The truth is that the growth of the different neighborhoods that today make up Tetuán has to do with the expansion of the city around the freight access road to the north of it and with the settlement of a large immigrant population and worker, who in many cases came to work in different projects: those of the Ensanche, on whose outskirts the neighborhoods of Cuatro Caminos and Bellas Vistas would grow, the subway works and the Paseo de Ronda (Avenida de Reina Victoria), of the City University, or the New Ministries. A growth similar to that of many other peripheral neighborhoods in the big cities of the time throughout the planet.

In short, one cannot properly speak of any founder of the neighborhood (which also are and were from the beginning several nuclei), unless we think of the working class and immigrant, the authentic architect of its growth.

Related Articles