Social movements in Argentina jump from the streets to the Government

At the end of October, in an act organized by the ruling coalition in Argentina, Peronism divided the stands of the Morón sports club stadium. One of the most important stands was reserved for La Cámpora, the Kirchnerist youth movement. Another for a local political group, Nuevo Encuentro, and the third for social movements. Their presence there shows the growing power of organizations that were born and strengthened in the streets but today are part of the Government, Congress and are also one step away from entering the largest workers' union in the country.

“In the nineties, the dismantling of the industrial world left a new subject, the unemployed worker. Argentina had never had unemployment as a relevant issue, but towards the year 2001, when the crisis broke out, we reached 25%. These sectors replicated the associative and union struggle tradition of the factory outside of it and found a place to organize in the popular neighborhoods”, explains the political scientist and CONICET researcher Francisco Longa on the origins of these movements.

The rise of these groups coincided with a serious crisis of political legitimacy, condensed in the cry of "that they all go away" that was repeated in each mobilization of the time. "At the end of the nineties, the anger was never channeled through politics but through other options," says Daniel Menéndez, a reference to Barrios de Pie. Social unrest broke out on December 19 and 20, 2001, with massive protests in the central Plaza de Mayo and its surroundings that were harshly repressed by the police forces, with a balance of 39 deaths and the subsequent resignation of the president, Fernando de the Rua.

The following year, Eduardo Duhalde, the country's fifth president in less than two weeks, created the Unoccupied Heads of Household plan, a state subsidy that reached some two million people. The objective was to guarantee social peace with the temporary relief of the economic situation of the most needy families, while waiting for the demand for labor to reactivate. "That did not happen and despite the growth, a universe of people who remained on the margins of the formal labor market was consolidated, what in Argentina we call the popular economy," adds Menéndez. Today the figure exceeds seven million people, according to the social leader.

Since then, the State has multiplied and diversified the subsidies along with the growth of poverty, which is above 40%. Among them are the Potenciar trabajo plans, a state contribution of almost 15,000 pesos (142 dollars at the official exchange rate) delivered to nearly a million people who work in recycling cooperatives, care tasks, food production, and the textile industry. Most of these cooperatives are linked to social movements, which allows them access to public funds and gives them the ability to mobilize on the streets and political influence.

“These social movements went from being organizations of the unemployed to all-terrain organizations, which operate in the almost traditional trade union arena, with the Ministry of Labor, move in the legislative field and not to mention at local scales; they generate their own candidates, referents that appear in the media and reach the electorate”, describes Longa, author of the book Historia del movimiento Evita. “The evolution is very remarkable, as seen in the formation of their own union,” he adds.

Recipe: Moroccan couscous and pomegranate : How to lock in the flavor and goodness of great food the ancient Chi... http://bit.ly/dEfSFU

— Daily Mail Online Mon Mar 21 08:52:42 +0000 2011

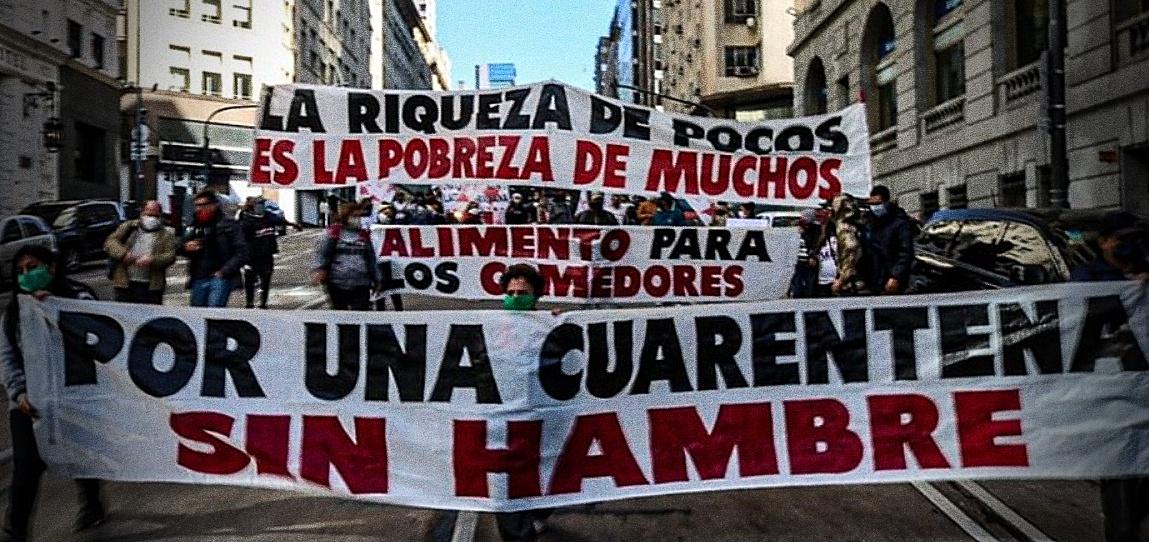

During the presidency of Mauricio Macri (2015-2019), social movements exercised harsh opposition from the streets. A little over half a year after his inauguration, on the day of the patron saint of labor, San Cayetano, they mobilized more than 100,000 people to demand “Land, roof and work” from the new president. In December 2017, the surroundings of Congress became the scene of a violent protest against an unpopular pension reform promoted by the Macrista government. Lawmakers were forced to adjourn the session due to a clash between protesters and police outside the compound.

The opposition to Macri united Peronism and the most related social movements chose to join, distancing themselves from those linked to left-wing parties. References such as Emilio Pérsico, from the Evita Movement, or Menéndez, from Barrios de Pie, entered the Executive formed in 2019 after Alberto Fernández won the presidential elections with former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as his second.

Pérsico is today in charge of the Social Economy Secretariat from which he controls social plans, while Menéndez spent two years as Undersecretary for Integration and Training Policies. Other social leaders, such as Juan Carlos Alderete, from the Classic and Combative Current, and Natalia Souto, from Barrios de Pie, fight for the rights of workers in the popular economy from the Chamber of Deputies. Juan Grabois, one of the best-known social leaders in Argentina, remains outside the institutions, but explicitly supports Kirchnerism.

The passage of social referents from the streets to the offices of power has caused significant tension with their bases. The organizations have gained control over public funds, but they must show their faces due to an economic situation that worsened greatly with the pandemic and is now worse than the one inherited from the Macri government. "This is one of the great dilemmas faced by officials who accompany the Government, but even so, the participation of social movements in the State does not deprive them of criticism," Longa points out, citing Dina Sánchez's questions as an example, one of the leaders of the Unión de Trabajadores de la Economía Popular (UTEP) union to the government project that seeks to integrate them into the formal labor market.

Two decades after its creation, social movements have diminished the role of traditional unions in the street, but not political influence. “Trade unionism is losing gravitation because it is an actor born in a certain labor society and if you have a high sector of the population in the informal sector, as is the case in Argentina, with 32%, it does not have the same weight as before. But the unions here are not regressing as in other countries because the presence of one union per branch is maintained, they maintain the monopoly of labor representation and continue to play a very important role”, says Ana Natalucci, a CONICET researcher and director of the Program Studies and research of the popular economy and technologies of social impact.

The next advance they plan is to enter the largest Argentine labor union, a wish that could come true this Thursday, at the CGT congress. "The entry of the UTEP in the CGT comes to renew the trade unionism, which has slower and more bureaucratic mechanisms," Longa emphasizes. Another difference with traditional unions has to do with the female presence in management positions: in the former they are dominated by men, while UTEP has gender parity in its leadership.

A few days before the legislative elections on Sunday, the social movements await electoral results that the polls predict are adverse for the ruling coalition. Since the defeat in the primaries on September 12, its militants have mobilized door to door to try to convince voters disappointed with the government coalition that they chose to stay at home. If the electoral failure is repeated and the economic horizon does not improve quickly, the pressure from the bases to return to the streets will grow.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS America newsletter and receive all the key information on current affairs in the region.

Related Articles